In Tenwow International Holdings Limited (In Liquidation) and Anor v PricewaterhouseCoopers (a Firm) and PricewaterhouseCoopers Zhong Tian LLP [2024] HKCA 1193, the Court of Appeal (“CA“) ordered a letter of request to be issued by the High Court of Hong Kong to the Shanghai High People’s Court. This request seeks the transfer of audit working papers from the Mainland to Hong Kong pursuant to the Arrangement on Mutual Taking of Evidence in Civil and Commercial Matters between the Courts of the Mainland and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (《關於內地與香港特別行政區法院就民商事案件相互委託提取證據的安排》) (“Mutual Arrangement“).

The case involves an audit negligence claim filed by the liquidators of the Tenwow group and one of its subsidiaries against PwC and PwC Zhong Tian (an accounting firm incorporated in the Mainland). The liquidators alleged that PwC Zhong Tian had breached its duties by failing to detect defalcations by way of prepayments made to three supplies and illegitimate financial assistance given to a non-group company related to a director and his associates.

In respect of the audit working papers, the liquidators requested PwC Zhong Tian to provide, inter alia, its working papers; however, PwC Zhong Tian contested that Mainland laws and regulations imposed a blanket prohibition on the unauthorised transfer of audit working papers outside of the Mainland.

Mutual Arrangement

Pursuant to Article 6 of the Mutual Arrangement, the scope of assistance that may be requested by a Hong Kong court in seeking the taking of evidence by a Mainland court under the Mutual Arrangement includes:

(a) obtaining of statements from parties concerned and testimonies from witnesses;

(b) provision of documentary evidence, real evidence, audio-visual information and electronic data; and

(c) conduct of site examination and authentication.

The Court’s Ruling

Pursuant to the Mutual Arrangement, PwC Zhong Tian applied to the Court of First Instance for a letter of request to be issued by the High Court of Hong Kong to the Shanghai High People’s Court. However, such application was rejected by Anthony Chan J on the basis that letters of request were normally issued for obtaining evidence from non-parties, or at most for taking the evidence of a party overseas, rather than for the production of documents and discovery. Further, Anthony Chan J held that obtaining approval from the Mainland authorities did not fall within the categories referred to in Article 6, rendering the Mutual Arrangement inapplicable.

In the appeal, the CA allowed the appeal and ordered a letter of request to be issued for the following reasons, among others:

(a) In a broad sense a letter of request is a formal written document through which a court seeks assistance from a court in another jurisdiction, either under a convention or out of comity and reciprocity. While typically used to obtain evidence from third parties, it does not preclude their issuance to aid a party in fulfilling its own discovery obligations. Therefore, it is not inappropriate in principle to use a court-to-court request procedure in aid of the production of a party’s own documents in light of a legal impediment in the foreign jurisdiction;

(b) A letter of request is only a request. Issuing a letter of request does not necessarily subordinate the court’s power to the penal laws of another jurisdiction. It is a matter of discretion based on the case’s specifics, with no requirement to disregard or prioritise foreign law. The court retains full control over its processes even after a request is issued;

(c) After reviewing the relevant Mainland law and regulations, the CA was cautious about making any firm findings of Mainland law due to absence of oral examination of the experts and a lack of expert evidence regarding the latest Mainland regulation. Nevertheless, the CA concluded that PwC Zhong Tian had demonstrated a real risk that it would be penalised in the Mainland if it simply handed over copies of the audit working papers to the liquidators in Hong Kong without prior approval from the Mainland authorities;

(d) The use of court-to-court procedure is justified, as any requisite approval for the transmission of audit working papers for judicial proceedings should be sought pursuant to the applicable mutual judicial assistance protocol;

(e) The Mutual Arrangement is intended to facilitate the efficient and certain acquisition of evidence for civil and commercial matters by litigants in both jurisdictions. Therefore, there is no reason to interpret the Mutual Arrangement so restrictively as to exclude the present application for approval from the Mainland authorities. The assistance sought through the letter of request falls within the scope of the Mutual Arrangement, and aligns with the policy of Mainland law; and

(f) Concerning the objection based on the submission of futility, the CA determined that, in the absence of any evidence detailing what transpired with the letters of request in previous cases or the reasons for their non-execution, the Court would not infer that a letter of request in the present case would be futile.

Takeaways

Audit working papers are essential documents for the fair disposal of a claim alleging auditors’ negligence. This case marks the first successful application for a letter of request to transfer the audit working papers in a contentious context, serving as a precedent for future cases involving the transfer of such documents from the Mainland to Hong Kong, particularly in audit negligence claims. The CA’s rulings indicate a more flexible interpretation of the Mutual Arrangement, which may foster enhanced cooperation in taking of evidence in civil and commercial matters between Hong Kong and the Mainland in future cases.

The full judgment can be accessed here.

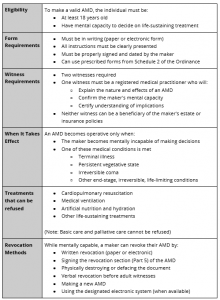

In response to Hong Kong’s evolving healthcare needs amid an aging population, Hong Kong has enacted the Advance Decision on Life-sustaining Treatment Ordinance (the “Ordinance”). Passed by the Legislative Council on 20 November 2024 and gazetted on 29 November 2024, this legislation establishes a comprehensive framework for advanced healthcare decisions. The implementation includes an 18-month transition period, allowing medical institutions, relevant departments, and organizations to update their protocols and systems, and conduct necessary staff training. To support implementation, the Hong Kong Academy of Medicine will introduce practice guidelines in the first quarter of 2025.

At its core, the concept of Advance Medical Directives is fundamentally rooted in patients’ rights to self-determination and human dignity. While patients have the right to make informed healthcare decisions, including refusing treatment, several critical questions arise: primarily, how can they exercise this right when their decision-making capacity becomes impaired, and what effect should their previously expressed wishes have on subsequent medical decisions?

To address these challenges, the Ordinance introduces two key advance decision instruments that empower individuals to make informed choices about their future medical care: (i) Advance Medical Directives and (ii) Do-Not-Attempt Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation orders. The legislation is particularly significant because, prior to its enactment, determining the validity and applicability of Advance Medical Directives in certain circumstances often involved legal uncertainties, placing medical professionals and patients’ family members in challenging situations.

Here are some key takeaways:

Advance Medical Directives (“AMDs”)

What is an AMD?

An AMD enables individuals to specify in advance their wishes regarding life-sustaining treatments for situations where they become mentally incapable of making such decisions. These legally binding documents provide healthcare professionals with clear guidance while respecting patients’ autonomy.

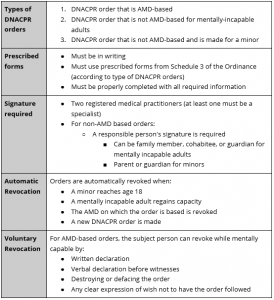

What is a DNACPR Order?

A Do-Not-Attempt Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation order is a legal document that directs healthcare providers not to perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation when a person experiences cardiopulmonary arrest. This means if the person’s heart stops beating or they stop breathing, healthcare providers will not attempt: (i) Chest compressions; (ii) Artificial ventilation; and (iii) Defibrillation

Transitional Arrangement

To ensure a seamless transition to the new legal framework, the Ordinance includes comprehensive transitional provisions for existing advance care planning instruments. Under these provisions, pre-existing AMDs that comply with the Ordinance’s requirements will remain valid. Nevertheless, individuals are encouraged to review their existing directives and consider updating them using the newly prescribed forms. Similarly, for pre-existing DNACPR Orders, the Hospital Authority will facilitate their transition to align with the Ordinance’s forms before the commencement dates, thereby ensuring the continued effectiveness of all advance care planning instruments.

Important considerations

The Ordinance marks a significant advancement in Hong Kong’s healthcare landscape, providing residents with greater autonomy over their end-of-life care while ensuring clear guidance for healthcare providers. When considering these advance decision instruments, individuals are recommend to:

By following these recommended steps, individuals can ensure that their advance decisions accurately reflect their wishes and can be effectively implemented when needed.

Access the full Ordinance here for more details.

In Hui Chun Ping v Hui Kau Mo [2024] HKCFA 32, the Court of Final Appeal (“CFA”) has handed down its judgment which provided important clarification on the applicability of a 6-year limitation period for “constructive trustees”.

The case of Hui Chun Ping concerns an agent (the Defendant) who has made a secret profit in breach of his fiduciary duty owed to the principal (the Plaintiff). The Plaintiff contended, among other things, that the Defendant was a “constructive trustee” who held the unlawful gains on constructive trust on his behalf. The key issue before the CFA was whether such a claim had been time-barred by virtue of section 20 of the Limitation Ordinance (“LO“).

Section 20 of the Limitation Ordinance

Under section 20 of the LO, all actions in respect of trust property are time-barred after a 6-year limitation period unless they fall within the exempted categories of section 20(1), to which no limitation period applies. The exempted categories under section 20(1) are:-

a) An action by a beneficiary “in respect of any fraud or fraudulent breach of trust to which the trustee was a party or privy“; or

b) An action by a beneficiary “to recover from the trustee trust property or the proceeds thereof in the possession of the trustee, or previously received by the trustee and converted to his use“.

The LO adopts the definition of a “trustee” under the Trustee Ordinance (Cap. 29), which includes a constructive trustee.

Ruling of the Court of Final Appeal

The Plaintiff’s contention that the Defendant was a “constructive trustee” within the ambit of section 20(1)(b) was rejected by the Court of First Instance, the Court of Appeal and finally confirmed by the CFA.

Having considered earlier authorities which pointed out the terminological confusion caused by judges who have used the term “constructive trustees” loosely, the CFA reiterates the distinction between:

a) “constructive trustees” who have previously accepted fiduciary duties in relation to the principal’s property prior to a subsequent breach of trust (e.g. where a defendant agreed to buy property for the plaintiff but the trust was imperfectly recorded) (“Category 1 trustees“); and

b) “constructive trustees” whose trusteeship arose solely as a result of their wrongful conduct (e.g. making a secret and unauthorised profit) (“Category 2 trustees“).

In line with the statutory intention and legal precedents, only Category 1 trustees are “constructive trustees” within the meaning of section 20(1) of the LO. They are “trustees” in the traditional sense in that they do not receive trust property in their own right but by a transaction which both parties intended to create a trust from the outset.

Properly characterised on the facts of this case, the CFA determined that the Defendant was a Category 2 trustee, thus falling outside of the scope of section 20(1) of the LO, resulting in the Plaintiff’s primary claim being time-barred. The consequential effect of this finding meant the Plaintiff’s alternative claims for (i) equitable compensation, and (ii) accounts and inquiries (which were either substantially in the same form of, or ancillary to the main claim) were equally rejected by the CFA as being time-barred.

Conclusion

In light of Hui Chun Ping v Hui Kau Mo [2024] HKCFA 32, beneficiaries and victims of wrongful conduct who are considering a claim in relation to a constructive trust are reminded to take heed of the distinction between Category 1 trustees and Category 2 trustees, and if applicable promptly take out an action before the statutory limitation period expires.

The full judgment of Hui Chun Ping v Hui Kau Mo can be viewed here.

Background

In December 2024, The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited (“HKEX“) completed its review of the issuers’ annual reports for the financial year ended 2023 and published the Review of the Issuers’ Annual Reports 2024 (the “Report“) as well as the Guide on Preparation of Annual Report (the “Guide“) in order to assist issuers in preparing future annual reports. This article summarises the main findings and recommendations in the Report and the Guide.

Review of the Issuers’ Annual Reports 2024

HKEX completed its review of the issuers’ annual reports for 2023 and published the Report which consolidated HKEX’s assessment of issuers’ compliance with specific disclosure requirements under the Listing Rules, adopting a thematic approach and selecting specific areas based on regulatory concerns. The main findings and recommendations are as follows:

(a) Review of Specific Disclosure Requirements

(i) Share schemes: Some issuers only disclosed the number of option shares that could be granted under the remaining scheme limit, but failed to include the option shares that have been granted but not yet exercised.

(ii) Significant investments: Some issuers failed to make the relevant disclosures for significant investments, as significant investments are not confined to securities in the company, but also include funds or wealth management products. If the materiality threshold is exceeded, they must be disclosed.

(iii) Performance guarantees and use of proceeds from fundraisings: Some issuers omitted to disclose the expected timeline for applying unutilised proceeds from fundraisings. Even in the absence of a definitive timetable for the deployment of these funds, issuers should still indicate an approximate timing for fund usage, and update investors through announcements and/or in subsequent financial reports when there is better clarity on the timeline.

(b) Thematic Review

(i) Financial statements with auditors’ modified opinions

(ii) Material lending transactions

(iii) Management discussion and analysis (MD&A)

(iv) Review of Financial Disclosure Under Prevailing Requirements (Including Accounting Standards)

Guide on Preparation of Annual Report

At the time of publishing the Report, HKEX also published this Guide which summarizes relevant key recommendations made by HKEX over the years after reviewing annual reports, as well as all disclosure requirements under the Listing Rules applicable to annual reports to assist issuers in preparing future annual reports.

(a) Mandatory disclosure requirements

(i) According to the Listing Rules (mainly Appendix D2) and guidance materials from HKEX, it is mandatory to disclose the following information in the annual reports:

(b) Recommended disclosure in specific areas from thematic review

(i) Financial statements with auditors’ modified opinions

(ii) Management discussion and analysis (MD&A)

(iii) Material asset impairments

(iv) Material lending transactions

(v) Performance guarantees

(vi) Newly listed issuers

(c) Financial disclosure under prevailing requirements

(i) Issuers should prepare the financial statements with a high standard of financial disclosure and ensure compliance with the applicable accounting standards.

(ii) When preparing financial information in annual reports, the following areas require particular attention: accounting policy information, judgements and estimates; revenue; business combinations; material intangible assets – impairment testing; valuation of Level 3 financial assets; credit risk disclosure on trade receivables; presentation of non-GAAP measures; and disclosure of possible impact of applying a new or amended standard in issue but not yet effective.

HKEX emphasised that other than the disclosure requirements set out in this Guide, issuers must ensure that their annual reports fully comply with all other relevant laws, rules and regulations, and industry standards, as applicable.

In addition, it is recommended that issuers and their audit committees adopt a proactive approach by communicating thoroughly with their auditors regarding audit plans, areas of focus for audits well before the end of that financial year in order to minimise the possibility of last-minute surprises.

In discrimination cases, when a court finds that an individual has suffered discrimination, it may award damages for “injury to feelings”. This type of compensation differs from economic losses, such as lost wages or incurred expenses. It specifically recognizes the emotional harm, humiliation, and distress that an individual may suffer due to discrimination.

The Hong Kong courts utilise established guidelines to quantify such damages, often referred to as “Vento bands”, named after a landmark UK case. The Vento bands have been considered and accepted by the Court of Appeal in Hong Kong and provide a range of monetary compensation that is categorised as follows:

To ensure that compensation awards maintain their intended remedial value, the bands require periodically updates to reflect current economic conditions, including inflation.

It is also important to note that each case is unique, and the specific circumstances will always be taken into account when determining the appropriate level of damages. The court will consider factors such as the severity of the discrimination, its duration, and the psychological impact on the individual.

In the recent disability discrimination case in the District Court (陈詠琴 v 第一流行鋼琴教室有限公司 [2024] HKDC 2046), damages were awarded for “injury to feelings”. The Court took the opportunity to adjust the Vento scale bands for inflation as applied in Hong Kong.

The case involved a customer service officer at a piano learning centre who was dismissed due to her disability and related sick leave during her probation period, constituting an unlawful disability discrimination act under the Disability Discrimination Ordinance (“DDO“). The District Court ordered the employer to pay the employee HK$95,000 for injury to feelings and HK$48,000 for loss of income.

The Court’s Decision

The amount of damages for injury to feelings generally follows the scale established in the UK case of Vento v Chief Constable of West Yorkshire Police [2002] EWCA Civ 1871, i.e.,:-

(a)Top Band: £15,000 – £25,000;

(b) Middle Band: £5,000 – £15,000; and

(c) Bottom Band: £500 – £5,000.

The District Court in this case took into account the impact of inflation in Hong Kong and adjusted the amounts as follows:-

(a) Top Band: HK$285,000 – HK$475,000;

(b) Middle Band: HK$95,000 – HK$285,000; and

(c) Bottom Band: HK$9,500 – HK$95,000.

The District Court ruled that the discriminatory behaviour in this case was the most serious at the bottom band, or the lowest at the middle band, and decided that the amount of damages for injury to feelings should be HK$95,000 for the following reasons:-

(a) the discriminatory act was one-off in nature;

(b) throughout her employment, the employee maintained a good relationship with her colleagues, performed satisfactorily, and received no complaints;

(c) the employer’s abrupt dismissal of the employee just days before the expiry of the probationary period appeared to be a deliberate attempt to circumvent the obligation to provide a one-month notice or compensation in lieu;

(d) there were only 8 days between the employee’s notification of her disability and her dismissal. Given that she had just been diagnosed, she was experiencing significant worry and anxiety, which compounded the employer’s discriminatory treatment during this vulnerable time;

(e) following her dismissal, the employee experienced emotional distress and stress, leading to disrupted sleep and hindering her rehabilitation progress; and

(f) the employer never issued an apology and has expanded its business after the claim was filed, as if rubbing salt in the employee’s wounds.

Takeaways

This decision reinforces the legal protections against disability discrimination and raises awareness among employers regarding their responsibilities under the DDO. Employers must recognize that dismissing an employee due to his or her disability is unlawful, regardless of whether the employee is on probation or not. The increase in compensation inevitably leads to greater potential liability for employers and other respondents in successful discrimination cases, depending on the applicable compensation band.

Employers are advised to seek legal advice to ensure compliance with the DDO and to understand their rights and responsibilities when it comes to managing employees with disabilities. Regular legal reviews can help mitigate risks associated with discrimination claims.

The court decision can be accessed here.

See news from our global offices