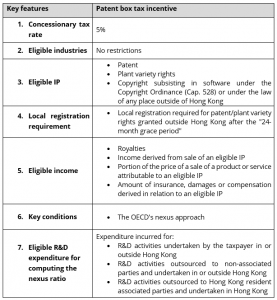

The Hong Kong government has introduced a new “patent box” tax incentive through the Inland Revenue (Amendment) (Tax Concessions for Intellectual Property Income) Ordinance 2024. This new ordinance officially came into effect on 5 July 2024, allowing taxpayers to apply for the incentive retroactively from the 2023/24 year of assessment.

Under this new regime, qualifying profits derived from eligible intellectual property (IP) will be subject to a concessionary tax rate of 5%, significantly lower than Hong Kong’s standard profits tax rate of 16.5%. Eligible IP includes patents, copyrighted software, and new plant variety rights. Notably, eligible IP registered worldwide can qualify for the incentive, provided the profits are sourced in Hong Kong.

To benefit from the tax concession, the eligible IP must be primarily developed by the taxpayer. If the research and development (R&D) process involves acquiring IP or outsourcing R&D activities, the proportion of profits eligible for the concessionary rate may be reduced. Additionally, enterprises will need to obtain local registration for their non-Hong Kong patent and plant variety right to enjoy the concession, a requirement that will come into force two years after the implementation of the “patent box” tax incentive.

The key amendments are summarized as follows:

The Commerce & Economic Development Bureau stated that this regime encourages enterprises to increase their R&D activities and promotes IP trading, thereby strengthening Hong Kong’s competitiveness as a regional IP trading center. The government views this initiative as a crucial step in enhancing the city’s overall innovation and technology landscape.

For access to the full text of the Ordinance, please refer to the following: https://www.gld.gov.hk/egazette/english/gazette/file.php?year=2024&vol=28&no=27&extra=0&type=1&number=17

In the recent case of Joint and Several Liquidators of Yes! E-Sports Asia Holdings Limited (In Liquidation) v Holman Fenwick Willan (A Firm) [2024] HKCFI 1197, the court criticized the respondent law firm for imposing unwarranted conditions for compliance with a document production request made by the liquidators of their former client. The liquidators stood in the shoes of the former client upon its liquidation, and there can be no question that the client is entitled to the return of its own files. The court further made clear that there is no basis for the recipient of a document production request to insist on payment on account before compliance.

See full judgment here.

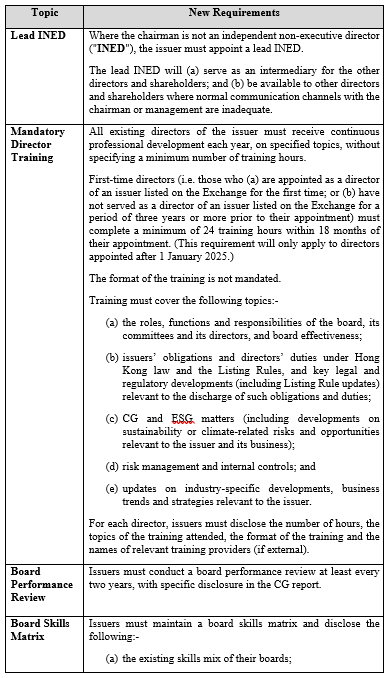

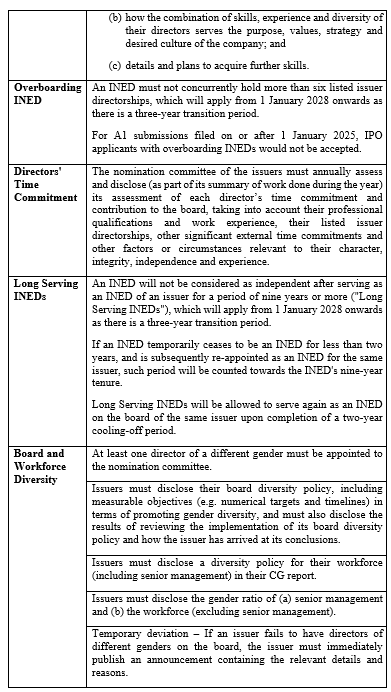

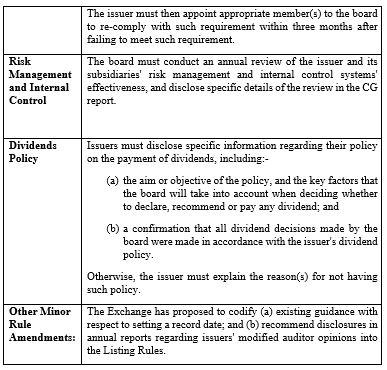

On 14 June 2024, the Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited (“Exchange“) published a consultation paper proposing amendments to the Corporate Governance Code (“CG Code“) and related Rules governing the listing of securities on the Exchange (“Listing Rules“) (“Consultation Paper“).

The proposals set out in the Consultation Paper aim to strengthen the corporate governance (“CG“) of listed companies, with a focus on board effectiveness and independence, diversity, risk management and capital management.

If the proposals below are adopted, it is expected that they will come into effect on 1 January 2025, and apply to CG reports and annual reports published from the year 2026 onwards. A three-year transition period is expected to be put in place for certain proposals as stated below.

The key proposals are summarised as follows:-

Introduction

Keepwell deeds are executed by PRC-incorporated companies undertaking to ensure that their offshore subsidiaries are solvent and will have sufficient liquidity to make payments to foreign creditors under offshore bonds issued by the offshore subsidiaries as they fall due. While the terms of keepwell deeds create an obligation on the onshore parent to provide financial support to the offshore subsidiary, keepwell deeds do not provide for a direct debt claim by a creditor against the onshore parent for any due but unpaid obligation of the offshore subsidiary. Instead, a creditor may only claim breach of contract against the keepwell provider for failing to perform its obligations under the keepwell deed.

This article examines the recent developments in Hong Kong on the law relating to keepwell deeds as illustrated in the case Re Peking University Founder Group Company Limited [2024] HKCA 445.

Factual background

Peking University Founder Group Company Limited (“PUFG“), being a PRC-incorporated holding company of a group of companies, entered into 4 keepwell deeds (“Keepwell Deeds“) in relation to the bonds issued by its subsidiaries, namely Nuoxi Capital Limited (“Nuoxi“) and Kunzhi Limited (“Kunzhi“), in 2017 and 2018. The bonds issued by Nuoxi and Kunzhi were guaranteed by HongKong JHC Co Limited (“HKJHC“) and Founder Information (Hong Kong) Limited (“FIHK“) respectively.

Under the Keepwell Deeds, it was provided, amongst other things, that:-

In 2020, PUFG was ordered by the PRC court to commence reorganization and a liquidation group was appointed to supervise the reorganization. Subsequently, Nuoxi and Kunzhi defaulted under the bonds, whereas HKJHC and FIHK did not honour their respective guarantees. Nuoxi, Kunzhi, HKJHC and FIHK were all put in liquidation since 2021. The liquidators of Nuoxi, Kunzhi, HKJHC and FIHK commenced actions against PUFG, claiming that it had defaulted on its obligations under the Keepwell Deeds, entitling it to damages.

The Court of First Instance (“CFI”)’s decision

In Re Peking University Founder Group Company Limited [2023] HKCFI 1350, the CFI found that since PUFG had been put into reorganisation, there was “no realistic likelihood” that regulatory approvals for transfers necessary to pay liabilities under the bonds would be approved. It was held that although PUFG took no steps at any time to obtain the approvals, consents, licences, orders, permits or any other authorisations as might prove necessary to comply with its obligations under the Keepwell Deeds, the failure to make any effort to obtain them did not prevent it from relying on clause 2.2 (see above) because the necessary approvals could never have been obtained and it made no difference to the outcome.

The CFI dismissed the claims brought by Nuoxi, Kunzhi and HKJHC concerning post-reorganisation breaches on the foregoing basis and only granted declaratory relief in favour of FIHK as PUFG had been in breach of its Balance Sheet Obligation to FIHK before its reorganization.

Nuoxi, Kunzhi and HKJHC (collectively, “Plaintiffs“) appealed against the CFI judgment.

The Court of Appeal’s (“CA”) decision

The Plaintiffs raised 5 broad grounds of appeal, namely that the CFI judge:

The Relevant Approvals not always necessary

The CA ultimately allowed the Plaintiffs’ appeals on Ground 3 and granted the appropriate declaratory reliefs to the Plaintiffs. A proper construction of clause 2.2 of the Keepwell Deeds would mean that the Relevant Approvals are not always necessary for PUFG to perform its obligations under the Keepwell Deeds. The CFI judge had failed to consider the possibility of other modes of performance that would not require the Relevant Approvals, for example, issuing a new bond to refinance repayment of the existing bond; repurchase of onshore foreign direct investment, presumably denominated in a foreign currency; and making use of cash to support overseas investment or moving the fund offshore to support overseas project. The CA was of the view that had the judge considered these possibilities, he could not have been satisfied that PUFG had established that it would come within the escape clause in clause 2.2, because the Liquidity Payment Obligation could have been performed without the Relevant Approvals.

Whilst the CA rejected Grounds 1, 2, 4 and 5 raised by the Plaintiffs for various reasons, below are some of the observations made by the CA which are noteworthy.

The Balance Sheet Obligation

In relation to clause 4.1(i) of the Keepwell Deeds, the Plaintiffs contended that “[t]he liability under the Balance Sheet Obligation did not need to be established in an action or converted into a judgment debt in order to be provable in an insolvency. The quantum of that liability was the sum the plaintiffs required to meet their liabilities plus US$1. The reorganisation did not change the contractual rights of the plaintiffs, it only meant that the plaintiffs had different rights of enforcement“.

However, the CA rejected the Plaintiffs’ argument, and held that clause 2.2 must be taken into account in considering the question of breach, the purpose of which is to “prevent PUFG from being in breach in circumstances where it was unable to comply with its undertakings because of the need for and the absence of Relevant Approvals“.

To pursue a claim in relation to the Balance Sheet Obligation, there must be a breach of the ‘see to it’ obligation (meaning, in the context of guarantees, an undertaking by the guarantor that the principal debtor will perform his own contract with the creditor), which alone does not give rise to a claim for damages in the absence of a breach. The breach does not need to be established first in an action, so long as it is eventually shown to give rise to liability.

Breach of natural justice and pleadings

The Plaintiffs contended that the CFI judge acted in breach of natural justice and of their right to a fair trial, as the judge relied on the evidence and submissions in a subsequent case Re Tsinghua Unigroup Co., Ltd [2023] HKCFI 1572. The complaint was that the Plaintiffs were not given a fair or proper opportunity to make further submissions on the inconsistent and contradictory evidence in the trial of the subsequent. The CA quickly dismissed this ground of appeal on the basis that they were provided with the daily transcripts of the trial and could well ascertain what the witness had said in the subsequent trial and were free to make such submissions as appropriate.

Further, the Plaintiffs sought to challenge the CFI judge’s findings that the Plaintiffs’ pleadings did not entitle the court to find PUFG liable for failing to perform its obligations owed to the Plaintiffs prior to its reorganisation. The CA affirmed the CFI decision on this point, holding that the particulars of breaches pleaded by the Plaintiffs were all directed at breaches which took place after reorganisation had started.

Conclusion

The CA has effectively confirmed that the obligations under keepwell deeds are binding and enforceable in the Hong Kong courts. It has also provided useful guidance on a number of relevant issues such as the available modes of performance and the assessment of losses caused by breaches of keepwell deeds.

The full CA judgment is available at: https://legalref.judiciary.hk/lrs/common/ju/ju_frame.jsp?DIS=159968&currpage=T.

In CNG v G & G [2024] HKCFI 575, in dismissing the application to set aside the arbitral award by CNG, the Honourable Madam Justice Mimmie Chan warned that the legal professional should be wary of making unmeritorious challenges to set aside arbitral awards by “massaging” cases to fall under the exceptional grounds of challenge under Section 81 of the Arbitration Ordinance (Cap. 609).

The Court once again reminded litigants that arbitration is a consensual process of final dispute resolution to which parties have voluntarily agreed to, and the limited recourse parties have under the Arbitration Ordinance is not intended to afford them with an opportunity to ask the Court after the event to go through the award with a “fine-tooth comb” to look for defects and imperfections under the guise that the tribunal failed to act within its remit.

Section 81 of the Arbitration Ordinance

With the consensual nature of arbitration and the tribunal’s autonomy at the heart of arbitral process, the grounds to set aside an arbitral award as compared to appealing a judgment in Court actions are much narrower. Before delving into the facts and issues of the case, it is helpful to note the permitted grounds to set aside a Hong Kong arbitral award under Section 81 of the Arbitration Ordinance:

In addition to the above, Schedule 2 of the Arbitration Ordinance contains opt-in provisions which provide for application to the Court to challenge an award on the ground of serious irregularity and for appeals to the Court on questions of law.

Given the limited grounds for challenge as set out above, in CNG v G & G, CNG attempted to find loopholes and problems in the award by “massaging” its challenges as “CNG was unable to present its case“, “the arbitral procedure was not in accordance with the parties’ agreement“, “the Award deals with a dispute not contemplated by or falling within the terms of the submission to arbitration“, and “the Award is in conflict with the public policy of Hong Kong” ([20]).

Facts and Issues

The dispute was between shareholders of a company (“SIL“) which own and operate a mining and processing project, whereby CNG, a state-owned enterprise of the PRC, owned 65% of the shares of SIL and the 1st Respondent owned the remaining 35% of the shares of SIL. Relying on the arbitration clauses contained in both the share purchase agreement and the shareholders’ agreement entered into between the two Respondents, CNG and SIL, the Respondents commenced arbitration proceedings at the HKIAC against CNG for the main claims that CNG (a) failed to honour a right of first refusal conferred on the 1st Respondent under the shareholders’ agreement in respect of CNG’s purported transfer of its shareholding in SIL (the “Share Transfer Claim“); and (b) failed to obtain the unanimous approval of the board of SIL before shutting down certain operations of the mining and processing project.

Failure to deal with issues / give reasons

The Respondents argued in the arbitration that as CNG had issued a valid transfer notice which met the requirements of the shareholder’s agreement to be an offer to the other shareholders, CNG was bound to sell the shares to the 1st Respondent as the only other shareholder of SIL. In contrast, CNG posited that the offer was an independent offer made to a permitted transferee (CGG, an affiliate of CNG by virtue of its control), and did not constitute a transfer notice within the meaning of the shareholder’s agreement which would afford the 1st Respondent the right of first refusal. The tribunal found that CNG’s transfer notice constituted an offer, which was capable of acceptance and was accepted, and that CNG was bound to sell the shares to the 1st Respondent in accordance with the shareholders’ agreement.

Before the Court of First Instance, CNG’s complaints placed reliance on the failure of the tribunal to deal with key issues or give reasons for its decision on the matter ([23]). For example, CNG emphasised that only 24 paragraphs of the total 163 paragraphs of the award were devoted to the tribunal’s reasoning for its decision on the Share Transfer Claim ([24]). Further, the tribunal did not deal with all the issues listed on the agreed list of issues submitted by the parties ([25]).

In response, Chan J noted that a long prolix judgment or award does not mean that it must contain sound reasoning or analysis of an issue or decision made. Vice versa, a short document likewise cannot indicate that there is no good reasoning or answer to the issue raised for decision ([24]). Moreover, an award is to be read and understood in the context of how the case was argued before the tribunal. In this case, it was logical for the tribunal to deal with the relevance of CGG being a permitted transferee under the shareholders’ agreement first. A decision in favour of the Respondents on this issue would render it unnecessary for the tribunal to determine whether, in fact, CGG was a permitted transferee ([33]). As noted by Chan J at [26]:

“…the tribunal does not have to set out each step by which it reaches its conclusion, and a failure to deal with an argument or a submission made on or relating to an issue is not equivalent to a failure to deal with an issue. The tribunal is not required to deal with each issue seriatim, as it can deal with a number of issues in the composite disposal of them. A tribunal does not fail to deal with an issue if it does not answer every question that qualifies as an issue. It can deal with an issue where that issue does not arise in view of the tribunal’s decision on the facts or its legal conclusions. A tribunal may deal with an issue by so deciding a logically anterior point such that the other issue does not arise. If the tribunal decides all those issues put to it that were essential to be dealt with for the tribunal to come fairly to its decision on the dispute, it will have dealt with all the issues. So long as a decision on one argument suffices to resolve an essential issue, the tribunal does not have to consider all arguments canvassed upon the issue. Although awards often respond to parties’ submissions, such submissions do not dictate how the tribunal is to structure the disposal of the dispute referred to it…a list of issues is not an exam paper, and I would add that it is not an exam paper with compulsory questions for the tribunal to answer them all.“

Further, the Court was not concerned with whether the tribunal had come to the right decision for the correct reasons, or whether there was evidence to support its finding in the decision ([31]). The Courts’ approach was to read an award generously with minimal curial intervention. Only when there are meaningful and readily apparent breaches of the rules of natural justice which can cause actual prejudice (rather than to comb an award in order to assign blame or to find fault in the process), may it warrant the setting aside of an award ([27]).

Procedural decisions and alleged inability to present case

In relation to procedure, it was argued for CNG that the tribunal had imposed an unequal and tight timetable on CNG, and had allowed the Respondents last-minute ambushes by adducing late evidence and running an unpleaded case, which resulted in CNG not being able to present its case ([22], [66]).

Citing COG v ES [2023] HKCFI 294, Chan J reiterated that a case management decision of a tribunal is not a decision which the Court should highly interfere with, in the absence of what the Court can find to be a serious denial of justice. Nor is it the function of the Court to descend to a level of reviewing the minutiae of the procedure, while the tribunal is obviously in the best position to decide on the most appropriate and fair manner of proceeding with the arbitration in accordance with the Arbitration Ordinance ([67]). For instance, as Section 46 of the Arbitration Ordinance provides a “reasonable opportunity” (as opposed to “full opportunity” used in Article 18 of the Model Law) to the parties to present their cases, no party can claim the right to have all the time it needs to prepare for the hearing and what the Court seeks to enforce is a standard of due process which are generally accepted as essential to a fair hearing ([68]).

Takeaways

CNG v G & G serves as another reminder from the Hong Kong Court that it does not sit on appeal against the tribunal’s finding of fact or law, nor interfere with the tribunal’s proper exercise of its case management powers. If parties attempt to rehearse once again before the Court arguments already made before the tribunal, or have different counsel reargue its case with a different focus in the hope that the Court may come to a different conclusion, it is likely to attract indemnity costs being awarded by the Court without changing the outcome of the case.

See full judgment here.

See news from our global offices