For the third straight year, MinterEllison LLP is thrilled to be an industrial partner of the ARCH Community Outreach (“ACO“) Careers Program 2024, providing valuable job shadowing opportunities for local secondary school students to have a taste of working in the legal industry.

Following the conclusion of the ACO Careers Program 2024, our Paralegal (Pending Admission) Alan Sham and trainee solicitor Matthew Lau were invited to attend the Graduation Day and to sit on the panel of the presentation session on the 1st of September 2024, during which the students were given the opportunity to present what they have learnt throughout the Program, as well as network with representatives from various industrial partners of the Program.

We are pleased to have witnessed what the students have learnt throughout the Program, and are especially overjoyed to hear the feedback from students who have been with us during our 2-day work shadow programme on the 8th and 9th of August 2024. Participating in the ACO Careers Program is one of the many ways we at MinterEllison LLP contribute to the community, and we continue to look forward to future initiatives to foster the next generation of legal professionals.

In the recent case Green Light Multiplex Co Ltd v Lam Shi Yan [2024] HKCFI 2101, the Court of First Instance (“Court“) awarded over HK$2 million to an employer for breach of contractual and fiduciary duties by a former employee who wrongfully diverted business opportunities away.

Background

The 1st Defendant, Mr. Lam Shi Yan (“Lam“), was employed as the General Manager of the Plaintiff, Green Light Multiplex Co. Limited (the “Company“), which was originally engaged in the business of lighting components supply. Lam was hired to, among other things, expand the Company’s business into the project lighting business.

In this connection, Lam procured Abacus Lighting Limited (“Abacus“) to enter into an exclusive distributor agreement with the Company (the “EDA“). Under the EDA, the Company had the exclusive right to purchase, promote, and sell Abacus’ products and services in Hong Kong and Macau.

The relationship between Lam and the Company subsequently deteriorated in many respects. Lam alleged that Mr. Gordan Lai (“Lai“), the founder and Managing Director of the Company, stripped him of his powers and responsibilities through, for example, firing Lam’s subordinate without consulting him in advance. Lam contended that he had no choice but to resign given that the trust and confidence of the employment relationship had been undermined.

On the other hand, the Company, among other things, alleged that Lam wrongfully procured Abacus to breach the EDA, causing the Company to lose its exclusive distributorship to Pinetum Lighting Limited (“Pinetum“), a competitor of the Company which Lam later joined (although Lam denied that he had ever been employed by Pinetum). As a result, the Company lost further business opportunities in various construction projects.

In the circumstances, the Company claimed against Lam for breach of various implied terms of his employment contract and his fiduciary duties owed to the Company, which gave rise to loss of business opportunities and profits.

Implied terms of Lam’s employment agreement

Both the Company and Lam contended that certain terms had been implied into Lam’s employment contract. The Court accepted the Company’s case that the following duties owed by Lam were indeed implied into his employment contract: (1) a duty of fidelity and good faith; (2) a duty not to divert business opportunities; (3) a duty not to solicit customers; (4) a duty not to disclose confidential information; and (5) a duty not to use information obtained in the course of or as a result of his employment with the Company to the detriment of the Company.

The Court also accepted Lam’s case that there was an implied term that he would not be demoted, provided that the change of title would lead to a fundamental change to the whole nature of the job.

Fiduciary duties owed by Lam to the Company

The Court held that in determining whether an employee who is not a director owes fiduciary duties to the employer, it is necessary to identify with care the particular duties undertaken by the employee, and to ask whether in all the circumstances he has placed himself in a position where he must act solely in the interest of his employer. It is only once those duties have been identified that it is possible to determine whether any fiduciary duty has been breached. An analysis is therefore required as to whether in all the circumstances, and by reference to the specific contractual obligations, the employee has undertaken to act solely in the employer’s interests.

Here, considering the two factors below, the Court had no hesitation in concluding that Lam, as the General Manager, owed fiduciary duties to the Company, even if he was not a director of the Company:

Diversion of business opportunity and breach of duties by Lam

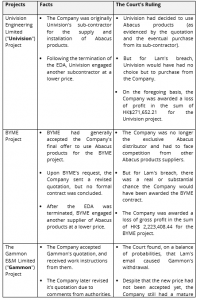

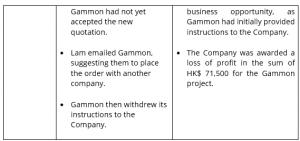

After considering a multitude of factual evidence adduced by the parties, it was held, among other things, that:

Takeaways

Apart from the general duty of fidelity and good faith that all employees owe to the employer, employees of sufficient seniority may also owe fiduciary duties to their employer if they have undertaken to act solely in the interest of the employer under the employment contract, notwithstanding that they are not directors. In general, fiduciary duties are higher and stricter than duty of fidelity.

Further, even in the absence of post-termination confidentiality obligations and restrictive covenants (which are commonly provided for in employment contracts to prevent employees from joining a competitor and soliciting business from former clients immediately after termination), the Court is ready to award damages to the employer if an employee’s conduct is found to be in breach of the implied terms of his/her employment contract and/or fiduciary duties owed to the ex-employer.

The full judgment can be accessed here.

On 23 August 2024, the Court of First Instance of the High Court (“Court“) in ING Bank N.V. v Industrial and Commercial Bank of China Limited [2024] HKCFI 2220 dismissed the defendant’s application for proceedings to be stayed in favour of Xi’an Intermediate People’s Court (“Xi’an Court“) on the ground of forum non conveniens (“FNC“).

The judgment contained a helpful summary of the principles governing FNC challenges and in particular where foreign law is said to apply to the matters in dispute.

Background

The plaintiff, a well-known international bank and one of Europe’s largest, was the vendor’s banker in a series of international sale of goods transactions with a total value of around US$171 million. The defendant is one of the largest banks in the world.

The payment terms for the transactions were DP (documents against payment) at sight. Pursuant to this arrangement, the documents of title and other commercial documents were delivered by the plaintiff (as the remitting bank) to the High-Tech Industries Sub-Branch of the defendant (“HTI-SB“) (as the collecting bank) for collection of the purchase price from the purchaser. The International Chamber of Commerce (“ICC“) Uniform Rules for Collections 522 (“URC“) were incorporated into the contract between the plaintiff and the defendant.

The plaintiff claimed that the defendant acted contrary to the collection instructions given to its branch HTI-SB and released the documents to the purchaser without collecting the purchase price. The defendant denied that it was required to act in accordance with the vendor’s direct instructions and relied on course of dealings and applied for proceedings to be stayed in favour of Xi’an Court.

Principles on FNC

The Court applied the test of FNC summarised in SPH v SA [2014] 17 HKCFAR 364 at [51] as follows:-

(a) The single question to be decided is whether there is some other available forum, having competent jurisdiction, which is the appropriate forum for the trial of an action, ie, in which the action may be tried more suitably for the interests of all the parties and the ends of justice?

(b) In order to answer this question, the applicant for the stay has to establish that first, Hong Kong is not the natural or appropriate forum (‘appropriate’ in this context means the forum which has the most real and substantial connection with the action) and second, there is another available forum which is clearly or distinctly more appropriate than Hong Kong. Failure by the applicant to establish these two matters at this stage is fatal.

(c) If the applicant is able to establish both of these two points, then the plaintiff in the Hong Kong proceedings has to show that he will be deprived of a legitimate personal or juridical advantage if the action is tried in a forum other than Hong Kong.

(d) If the plaintiff is able to establish this, the court will have to balance the advantages of the alternative forum with the disadvantages that the plaintiff may suffer. Deprivation of one or more personal advantages will not necessarily be fatal to the applicant for the stay if he is able to establish to the court’s satisfaction that substantial justice will be done in the available appropriate forum.

The Court’s Analysis

Appropriate Forum

As a first step, the Court looked for the forum which has the most real and substantial connection with this action taking into account the following factors:

Governing Law

The defendant asserted that Chinese law governed the relationship between the plaintiff and defendant and so the issue of governing law was also a key issue in the application. Nonetheless, the Court agreed with the plaintiff that (a) the Court would not make a final decision on proper law, which may be revisited at trial; (b) the Court would consider the proper law to assess the appropriate forum; and (c) if there is a good arguable case that Hong Kong law is the proper law, then it should follow that Hong Kong court is the appropriate forum.

In determining whether Hong Kong has the closest and most real connection with this action, the Court considered the following factors:

After evaluating the above factors, the Court believed that there is a good arguable case that Hong Kong law is the proper law because Hong Kong has the closest and most real connection with this action.

Accordingly, although the Court accepted that the Xi’an Court is perfectly capable of dealing with international transactions of the present type, the Court concluded that Hong Kong is the appropriate forum which has the most real and substantial connection with this action and it was not satisfied that Xi’an Court is clearly or distinctly more appropriate forum to hear this action.

Takeaways

This case provides helpful guidance on the jurisdictional disputes and conflict of law issues where the parties have not incorporated a jurisdiction or governing law clause in their contracts as is common in documentary credit and collection arrangements between trade finance banks.

Jurisdiction disputes of this nature can often be avoided by incorporation of suitably drafted jurisdiction or arbitration and governing law clauses in transaction documents.

Please see full judgment here.

George Tong and Ada Luk, our partners in our Corporate Team, have contributed to the Practice Note for Thomson Reuters’ Practical Law Global, outlining the statutory requirements to keep and maintain registers and other records for private limited companies incorporated in Hong Kong. The note can be accessed here: Company Records and Registers in Hong Kong

We have an outstanding team of lawyers and company secretarial services unit, who will be able to advise on and help you navigate regulatory compliance and corporate governance matters. Should you have any enquiries or require assistance in this aspect, please do not hesitate to contact us.

* Reproduced from Practical Law with the permission of the publishers. For further information, please visit www.practicallaw.com.

We are pleased to announce Ada Luk and Iris Cheng’s promotion to Partners at MinterEllison LLP. The promotion of Ada and Iris brings the firm’s number of Partners to 21.

Ada and Iris have shown unwavering commitment to our firm’s growth. Please join us in extending heartfelt congratulations to both Ada and Iris on reaching this significant career milestone.

See news from our global offices